Lent is a season of preparation before Easter, observed for about 40 days in many Christian traditions, but its exact dates change every year because Easter itself is a movable feast tied to the spring equinox and the lunar cycle. In most Western churches, Lent begins on Ash Wednesday, six and a half weeks before Easter, and traditionally excludes Sundays from the count, so the 40 days are spread over a longer calendar period.

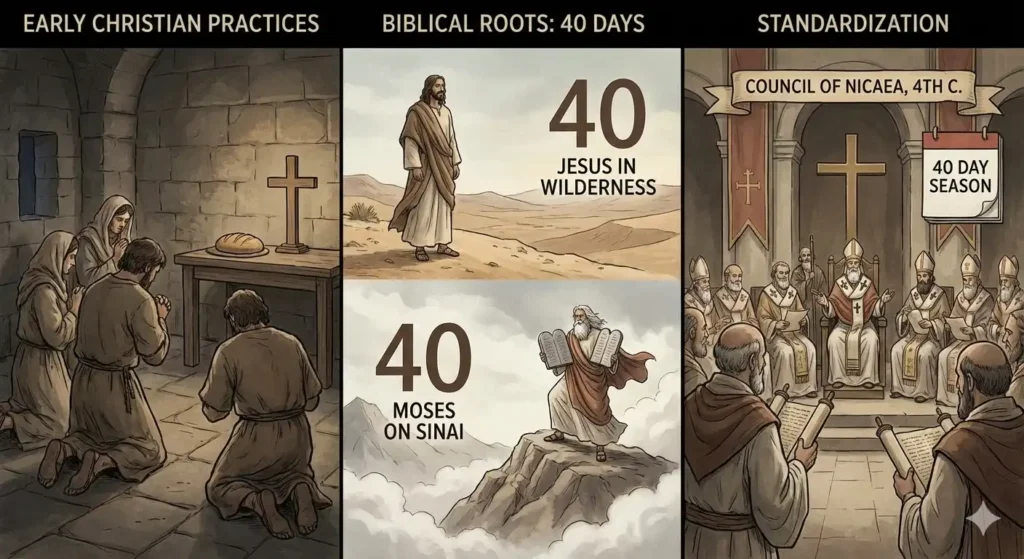

The First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE formalised the method for calculating Easter as the first Sunday after the first full moon following the vernal equinox, meaning Easter can fall between late March and late April in the Western calendar. Once Easter is fixed for a given year, churches count back to set the start of Lent, and since the early Middle Ages many Western Christians have begun it on a Wednesday to allow 40 penitential days plus six Sundays as feast days. In Eastern churches, Great Lent starts earlier, on the Monday of the seventh week before Easter, and ends on the Friday before Holy Week, with Saturdays and Sundays included but often observed as relaxed fast days rather than full‑fast days.

What are the origins of Lent as a Christian season?

The season of Lent grew out of early Christian practices of fasting and preparation before Easter, rooted in biblical themes of 40‑day periods of prayer and self‑denial such as Moses on Mount Sinai and Jesus’ 40 days in the wilderness. Historians and theologians note that some form of pre‑Easter fasting seems to have been observed from very early in the Church’s life, but it was not standardised as a 40‑day season across the Christian world until around the time of the Council of Nicaea in the fourth century.

Scholars outline several main theories on how the 40‑day pattern took shape: one view holds that it was directly created as a unified observance at Nicaea; another traces it to an Egyptian post‑Epiphany fast; and a third suggests that multiple local fasting traditions were gradually harmonised into a single Lent by that period. Over time, Lent became closely linked to the preparation of adult converts for baptism at Easter, as well as a period of public penance for Christians seeking reconciliation after serious sins, giving the season a dual focus on catechesis and repentance.

By the late sixth and early seventh centuries, popes such as Gregory I had a decisive influence on the shape of Lent in the Western Church, including regularising the start date so that the calendar provided exactly 40 fasting days before Easter. Early rules in the West were strict, often limiting the faithful to one meal a day in the late afternoon or evening and prohibiting meat, fish and dairy, reflecting an intense understanding of Lent as a time to discipline the body and turn more fully towards God.

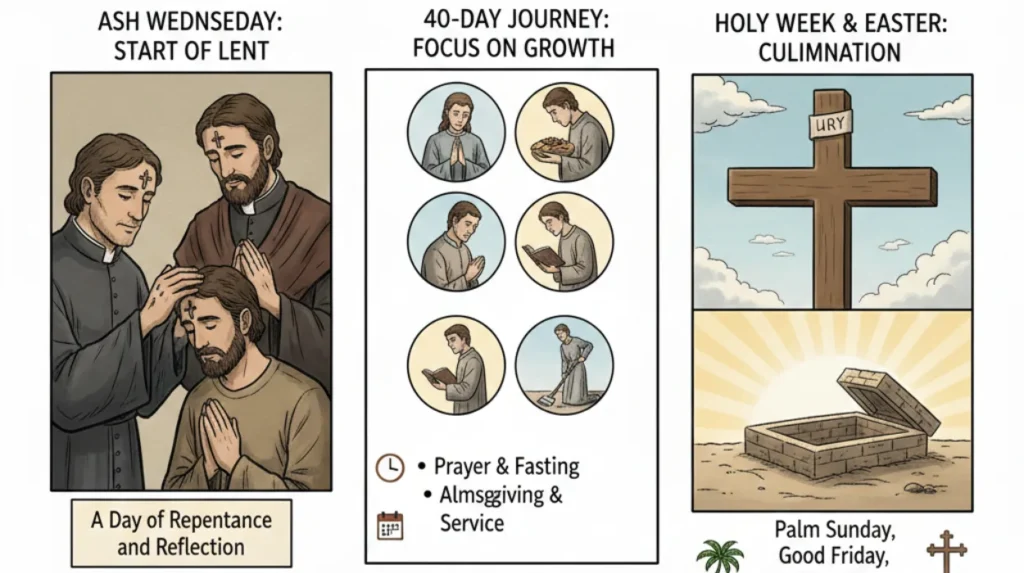

How do Ash Wednesday, Palm Sunday and Holy Week structure the Lenten journey?

Ash Wednesday marks the formal beginning of Lent in most Western Christian denominations, introducing the themes of mortality, repentance and renewal that shape the entire season. In many churches, worshippers attend a special service at which a minister or priest traces a cross on each person’s forehead with ashes, often saying words such as “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return,” drawing directly on biblical language about human frailty.

Historically, the ashes used for this rite are commonly made by burning palm branches blessed in the previous year’s Palm Sunday services, linking the beginning of Lent with Holy Week and the events leading to Jesus’ crucifixion. The sign of the cross in ashes serves as a public and personal symbol of repentance, and many Christians leave the mark on their foreheads for the rest of the day as a visible reminder of their commitment to the disciplines of Lent.

Palm Sunday, which falls on the Sunday before Easter, opens Holy Week and commemorates Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem when crowds greeted him by spreading cloaks and palm branches in his path. Churches across the world distribute palm branches or substitutes, invite congregations to join in processions, and recall the contrast between the celebratory welcome of that day and the suffering and death that follow later in the week.

Holy Week itself is the final, most intense phase of Lent, during which Christians retrace the last days of Jesus’ earthly life, including the Last Supper, his betrayal, trial, crucifixion and burial. In many traditions, Maundy Thursday services remember the institution of the Eucharist and the commandment to love one another, Good Friday focuses on the crucifixion through solemn liturgies or Stations of the Cross, and Holy Saturday is kept as a day of quiet vigil before the Easter celebration of the resurrection.

Who observes Lent and in what ways do traditions differ?

Lent is most widely observed among Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox Christians, Anglicans and many Protestants, though the extent and style of observance varies significantly between and within these communities. In the Roman Catholic Church, Lent in the modern Roman Rite runs from Ash Wednesday until the evening of Holy Thursday, forming a 44‑day liturgical season, while traditional fasting obligations extend through Good Friday and Holy Saturday so that the faithful still experience 40 days of fasting.

Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic churches observe what is often called Great Lent, beginning on Clean Monday (the Monday of the seventh week before Easter) and concluding before Holy Week, within a broader framework of pre‑Lenten and post‑Lenten practices. In these traditions, fasting disciplines are typically stricter, with many believers abstaining from meat, dairy and sometimes oil and wine on many days, and the liturgy shifts to emphasise themes of repentance, spiritual struggle and divine mercy.

Among Anglicans, Lutherans, Methodists and other mainline Protestants, Lent is commonly observed through special services, Bible readings, and voluntary acts of self‑denial or charity rather than uniform, church‑wide fasting regulations. Evangelical and free‑church communities are more mixed: some congregations embrace Lenten practices as a helpful spiritual discipline, while others downplay or omit the season because they see it as overly formal or not explicitly commanded in Scripture.

Outside historic churches, cultural awareness of Lent is also widespread in many countries with Christian heritage, where even those who are not practising Christians may speak of “giving something up for Lent” or notice public traditions such as Ash Wednesday ashes and pre‑Lent carnivals like Mardi Gras or Shrove Tuesday. This broad recognition reflects Lent’s long influence on social rhythms, from food customs to school calendars, in different parts of Europe, the Americas, Africa and beyond.

What fasting rules and spiritual practices shape Lent?

Traditional Lenten fasting rules emerged over centuries and differ by church and region, but they share a basic aim of fostering repentance, self‑control and deeper focus on prayer and charity. In the medieval Western Church, many Christians were expected to eat only one full meal a day after mid‑afternoon, abstain from meat, and often avoid dairy and eggs throughout the season, creating a demanding physical discipline.

Modern Roman Catholic rules in many countries are less strict but still retain a clear structure: Ash Wednesday and Good Friday are days of fasting and abstinence from meat for adults within specified age ranges, while all Fridays in Lent call for abstinence from meat or another penitential practice. Eastern Orthodox practice typically goes further, with a common pattern that excludes meat and dairy for most of Lent and sets out additional days of stricter fasting, though levels of observance can vary according to personal health, pastoral guidance and local custom.

Alongside dietary restrictions, many Christians adopt personal Lenten disciplines such as giving up particular luxuries, reducing entertainment or social media use, increasing daily prayer or Bible reading, and committing to acts of generosity or service. Rather than treating fasting as an end in itself, churches encourage believers to see these sacrifices as ways to become more attentive to God, more compassionate towards others, and better prepared to enter into the mysteries of Holy Week and Easter.

In some places, there is also a strong link between Lent and works of mercy, with congregations organising special charity drives, visiting the sick or isolated, or supporting relief projects during the season. Taken together, the fasting rules and spiritual practices of Lent are meant to echo Christ’s own path of humility and self‑giving love, inviting Christians to imitate that pattern in their own lives as they journey toward Easter.